This is an excerpt from a piece originally published in Ferment magazine in 2020, ostensibly about the “problem” of getting hospitality workers back to work during the Covid-19 pandemic—and the consideration of replacing human workers with automated services and even robots. Somehow, it is still relevant.

The hospitality industry in the UK might not be under the intense pressure of adhering to lockdown legislation anymore, but there are different, more difficult pressures to handle now. Closures are rife. Businesses just can’t stay open. I’ve had my say on this subject many times, but what I feel is forgotten (or avoided) in much discussion about the destruction and wilful, weaponised desertion of the industry by the Government is how with each closed restaurant, bar, pub, butty shop, or food truck goes the prospect of jobs available to those who need them. I’m not talking about long-term hospitality professionals. I’m talking about folks looking to supplement their income with a shift here and there. People who need work quickly in-between jobs. Hospitality has always been the go-to industry for these sorts of jobs—the jobs that keep those of us on a low-income going. We’re not just losing somewhere to relax after a hard day’s work. We’re losing the work, too.

That’s why I’ve chosen to publish this piece here it as it is, with no amends. I want to underline how nothing has changed. The hospitality industry has been struggling with the same issues for years.

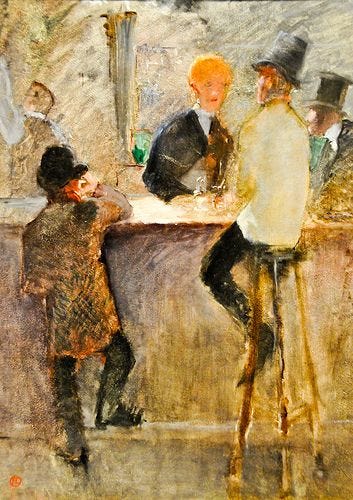

Robot Waiters

In my varied career I’ve been a potwash, a kitchen assistant (microwave cook), bar staff for various pubs including an infamous national chain and a local indie, and a waitress and server at a chip shop. The chip shop in particular holds deep memories for me. In debt and about to lose my room in a city I’d moved to three months earlier before having all of my life plans fall through, I walked in and begged for a job. They gave me one. Is working in a chip shop a dream role for a 23 year old journalism graduate? You forget that stuff when you need the money. Nobody is above a weekly paycheck. Journalism paid me nothing at that time, fish and chips kept me in rent and food. The team were fun to be around. The customers were, on the whole, pretty respectful. Which was the better career?

Part-time jobs in the food and drink sector are widely seen as an unofficial economic safety net. They’re there if you need a job, any job, fast — but due to the number of roles shrinking across the board, the image of handing an a4 CV across a bar and being thrown an apron in return is a fallacy. Didn’t I just tell you it happened to me? Yes. But that was nine years ago. The expectation remains, however, that if there’s nothing else, there’s barwork, there’s waiting tables. A minimum wage chipshop job might have worked for me at that time. It is not, and nor should it ever be considered to be, an effective replacement for a society that’s actually fit for purpose.

If you do a quick Google search right now to find out how to become more employable, you’ll find blog post after blog post listing the ways you could bag yourself a bar job, collect a ton of valuable skills and then slink off into the “real job” world. You will be hard pushed to find much mention of how those bar jobs can be fulfilling careers in themselves. You are much more likely to find subheadings like “how to make waiting tables sound good on a CV” than any information on how to work your way up to Maitre D’.

In a piece for her newsletter, food writer Alicia Kennedy said: “The flexibility of food service work gives it its pirate-like reputation, which results in both freedom and exploitation, low wages and the ecstasy of earned exhaustion.”

I feel like this can be extended to describe the long hours and antisocial nature of bar work. Do bar staff enjoy their work? I can’t speak for everyone, but I do. But can it also be the worst? Absolutely. And does it pay well? Hahahaha. Alicia Kennedy’s ironic contemplation of the “ecstacy” of hard work makes me laugh a bitter laugh. Because while we’re told that earning our rent with our sweat and smiles feels satisfying, when your wages are falling and your future is insecure, and people are openly considering whether your knowledge, enthusiasm and heart-beatingly-human body could be swapped out with a Roomba that can also carry plates, it doesn’t feel like you’re tying up the mainsail with a merry band of outlaws anymore. It feels like being taken for granted.

Other Stuff

More thoughtful writing on the loss of our pubs by Michael Deakin

Fred Garratt-Stanley for Time Out talks on how losing Wetherspoons still means losing well-used public spaces (note: I am referenced in this piece and very proud about it)

Celeb chefs, café owners and local MPs in Manchester have made a video to share their experiences and fears about the current hospitality industry crisis

My Stuff

I’m back on Twitter. It’s not a statement, I just got bored.

It’s my final PROCESS newsletter on Monday. Tip: Sign up to read them all over the week then cancel your pro-subscription and it’ll only cost you a couple of quid.

I’ve got rather a lot of stories on the go at the moment for Ferment, Glug, and Pellicle, so please keep an eye out.